California: Whales always return to sonar testing areas

February 7, 2019 Sonar free areas poor in foodUsing data from underwater robots, scientists have discovered that beaked whales prefer to feed within parts of a Navy sonar test range off Southern California that have dense patches of deep-sea squid. A new study, now published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, shows that beaked whales need these prey hotspots to survive and that similar sites simply do not exist in nearby "sonar-free" areas.

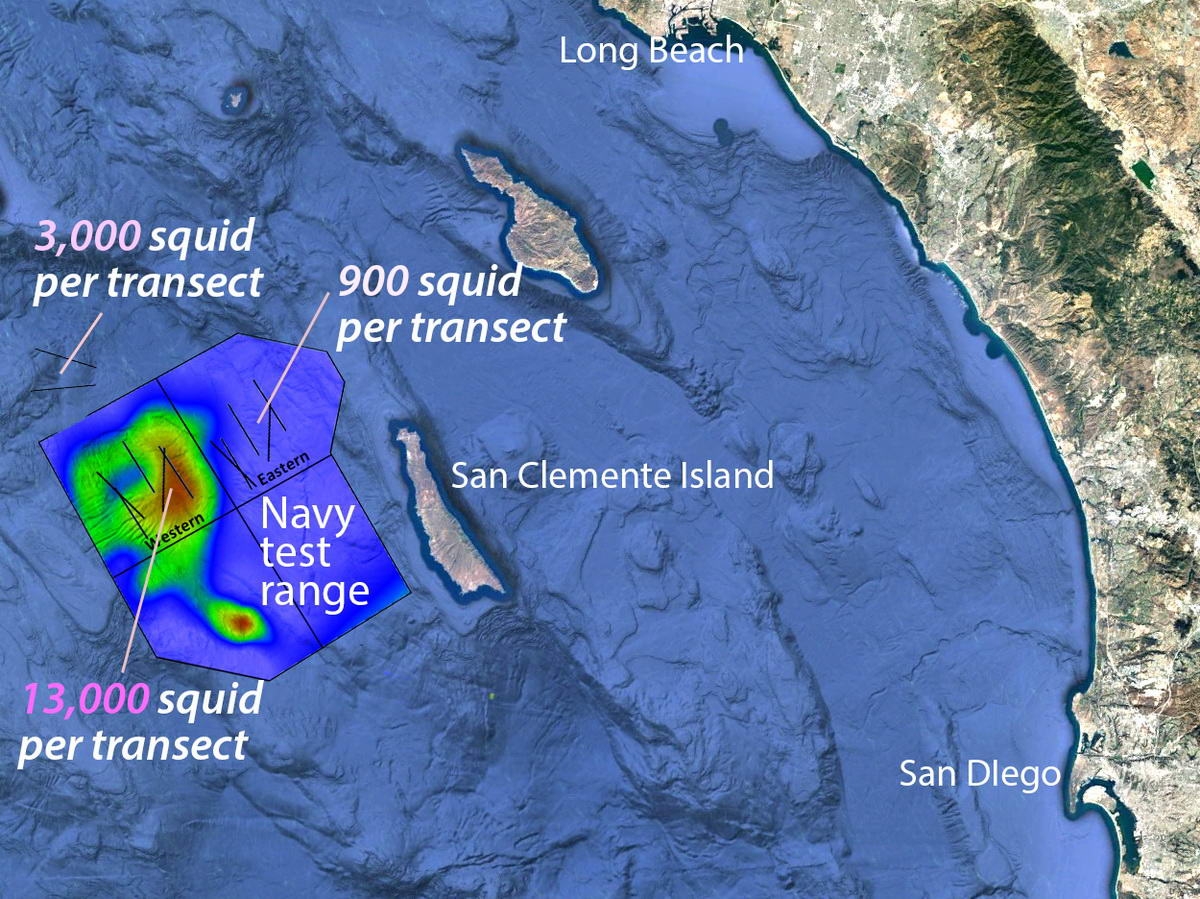

For decades, the US Navy has used powerful sonar during anti-submarine training and testing exercises in various marine habitats, including the San Nicolas Basin off southern California. Beaked whales are particularly sensitive to this type of military sonar. Following legal action by environmental activists, the Navy changed some training activities, created "sonar-free" areas and spent tens of millions of dollars over a decade to find ways to reduce the damage to beaked whales and other mammals.

New research led by Brandon Southall of the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Kelly Benoit-Bird of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute should help to better understand why the whales return to the test area despite the risks.

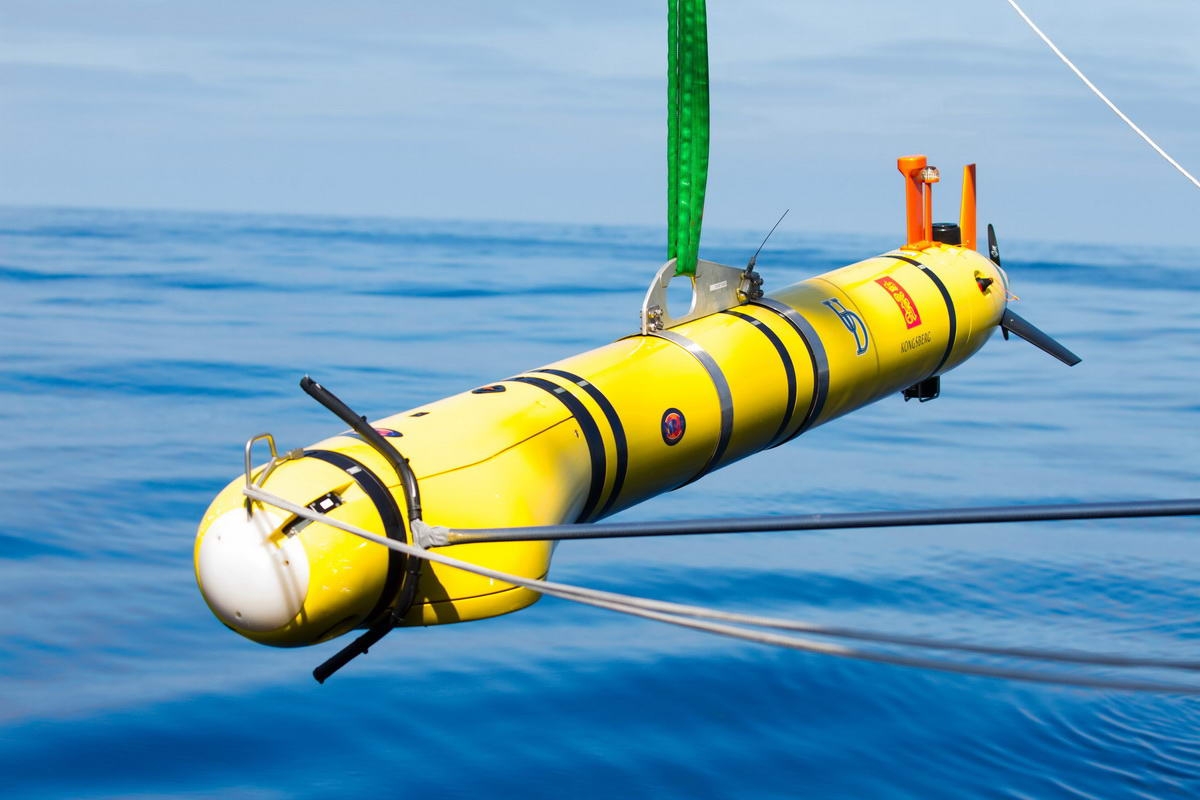

The researchers equipped an underwater robot with sonar to measure the abundance and size of deep-sea squids in various parts of the marine test area and in nearby waters. They also developed an "energy budget" for beaked whales, which shows the costs - in terms of time and calories - for hunting cuttlefish. This helped the researchers estimate how many dives the whales had to make in order to find enough food to survive in different areas.

"Beaked whales work very hard to get their food," says Benoit-Bird. Unlike many baleen whales with significant energy reserves, beaked whales cannot afford to spend too much energy on a dive that does not result in many cuttlefish to be caught. In areas where the concentration of prey is low, the beaked whales have to work harder and consume more calories, which makes the reproduction and rearing of the offspring much more difficult. Some of the areas studied were so low in prey concentrations that whales could probably not meet their basic energy needs if they hunted only there.

"The deep sea is not consistent and the whales know exactly where to hunt," adds Benoit-Bird. It turns out that part of the Navy testing area off southern California includes an area rich in octopus. In fact, squid were 10 times more common in the whale-preferred area. In this preferred area, the whales could get enough food by doing only one dive a day. In a nearby sonar-free area (founded on the idea that beaked whales could shelter in these areas during sonar tests), the whales had to do between 22 and 100 dives a day to get enough food.

"Our results have an impact on management," says Southall. "They provide direct information to the navy and federal agencies to better manage and protect important California habitats."

Link to the study: besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2664.13334.