Phantom hydrothermal vents in the deep sea

environmentmarine conservationmarine biologyoceanographyhydrothermal vents

0 views - 0 viewers (visible to dev)

Shells upon a black smoker in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between 5°S and 11°S. (c) ROV Kiel 600, GEOMAR

Research explain how organisms move between hydrothermal vents Highly specialised communities form at the hydrothermal vents in the deep sea. These communities are often hundreds or thousands of kilometres apart, causing marine biologists to wonder how larvae from the same species travel from one location to another.

Using oceanographic and genetic analysis of shells of the genus Bathymodiolus, an international team of scientists led by GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel have proven that there are as-yet undiscovered hydrothermal vents in-between the vents that serve as intermediate points.

Large flower-like tubeworms, foot-long clams, armoured worms and ghostly-looking fish are just some of the creatures that make up the unique diversity of the hot hydrothermal vents (also called black smokers) in the deep sea. The development of such ecosystems is linked to tectonic and volcanic activity at the ocean floor. Hydrothermal vents are often isolated and far from one another.

On the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, they are several hundred - even thousands - of kilometres apart. Many of the animals that live there remain underground once they reach adulthood. It is only during their larval stage that they are able to move from one location to another.

How the exchange between different populations is facilitated has remained a mystery amongst scientists, since the study of larval distribution in the ocean is virtually impossible.

This study, published in the international journal Current Biology, sheds some light on this phenomenon. " To detect the exchange between different hydrothermal vents at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, we used a combination of high-resolution genetic analysis and computer simulations of larval distribution. As an example, we used the shells of the genus Bathymodiolus, as these animals are a keystone species in hydrothermal ecosystems, " said GEOMAR's Dr Corinna Breusing in German. She is the author of the study.

For the participating oceanographers, the study was a first, as there was no data on flow patterns in the deep sea. Prof Dr Arne Biastoch from GEOMAR explained that they had used and adapted several ocean models before getting a realistic simulation of the larvae's drifting patterns. The modelling data was subsequently supported by molecular analysis — a combination that was seldom used, according to Dr Biastoch.

The team then developed molecular markers for the analysis of the relationships themselves, as the genetic data for Bathymodiolus had not been developed yet. In doing so, the researchers discovered that although an exchange between the different populations does exist, it does not occur within a single generation, as the larvae normally would not drift more than 150 kilometres.

GEOMAR's Prof Dr Thorsten Reusch said there must be undiscovered hydrothermal vents or habitats of a similar nature in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge that served as a kind of "stop", facilitating the exchange between different communities. He added that they referred to such "stops" as phantom stepping stones, as they do not know their location or how they were designed.

The results of the study are relevant because hydrothermal ecosystems contain sulphide deposits, known to be potential mineral sources for the future. Dr Breusing said that if the sulphide deposits have been degraded, appropriate protection zones must be set up, taking into account the migration routes of the unique inhabitants of the hot springs. He hopes that their work can lead to further research on other organisms and geographic regions, so that the information collected can be used to develop effective protection efforts.

More information: www.geomar.de

See also:

Hydrothermal Vent Discovered In Gulf Of California Exploring hydrothermal vents at Azores archipelago Researchers compile 3-D map of hydrothermal field in Pacific

The mussel species Bathymodiolus azoricus. (c) Jan Steffen, GEOMAR

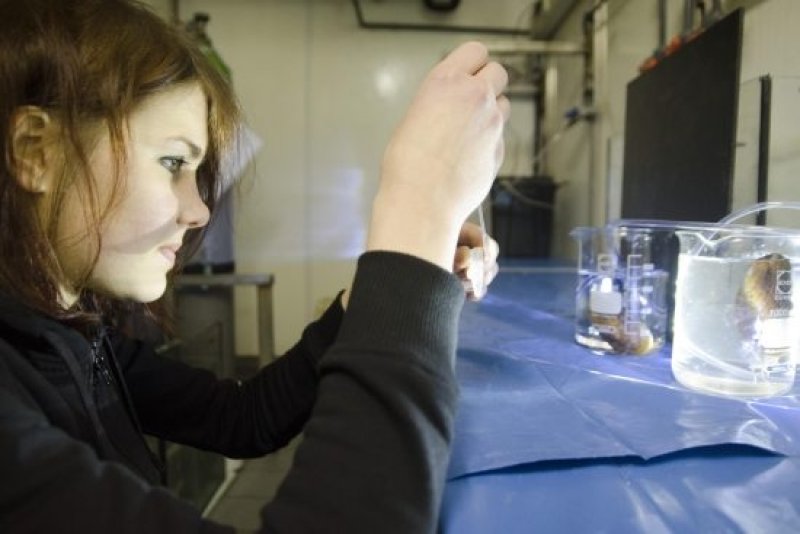

Dr Corinna Breuning, author of the study, in the climate chamber with Bathymodiolus azoricus. (c) Jan Steffen, GEOMAR