© A coral reef under normal pH conditions in the research area in Papua New Guinea. Photo taken from Fabricius, K. E. et al .: Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1, 165-169 (2011).

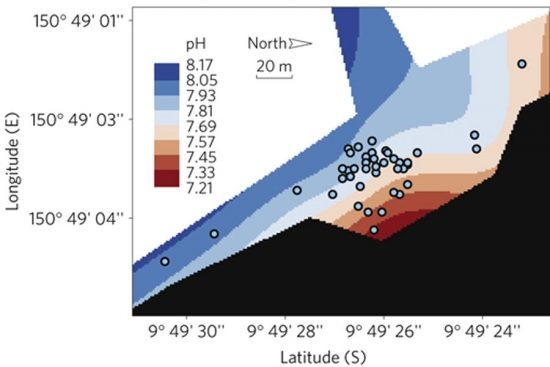

© Map of the research area with sampling locations and pH gradient. Graphic taken from Fabricius, K. E. et al .: Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1, 165-169 (2011).

Can corals sustain themselves against falling pH values?

August 8, 2016

GEOMAR scientists examine internal pH values of corals in Papua New Guinea

Tropical corals of the genus Porites have the ability to adjust their internal pH values, so as to produce calcium carbonate and grow under conditions of increased carbon dioxide concentrations, even for long periods of time. To understand this pH regulation in more detail, GEOMAR researchers analysed samples of this coral that have existed in natural carbon dioxide sources in Papua New Guinea for decades.

As the oceans absorb the man-made carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, its pH value is decreased. This change in the ocean’s chemistry has an effect on tropical coral reefs which can be measured in the laboratory or in short-term field experiments. Researchers from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel examined corals of the genus Porites growing at the volcanic carbon dioxide vents in Papua New Guinea, where they have become a dorminant species.

The team was led by Dr Marlene Wall, a marine biologist at the GEOMAR. She said that it was very difficult to foresee if tropical corals would survive global climate change as they were very sensitive to a rise in water temperature, ocean acification and pollution. She added in German that "the natural carbon dioxide vents give us the opportunity to study the scenario of the future. Previous studies have shown that Porites is among the winners. But up to now, no one knew how they manage."

The tropical hard corals maintain their internal pH at levels which they can produce calcium carbonate and continue to grow despite the higher concentrations of carbon dioxide and lowered pH values in the water. This gives them a significant advantage over many other types of coral species, enabling them to establish themselves under extreme conditions. Based on their observations, Dr Wall said that pH regulation was a key factor when it came to surviving under conditions of lowered pH values.

The team used the boron isotope method to get a better understanding of pH regulation. A laser was directed at the skeletons of corals, and the material that came off was analysed in a mass spectrometer. The researchers obtained information about the coral’s internal pH by examining the isotopic composition of the boron in the skeleton. "This method gives us new insights and allows for conclusions about the physiology of the coral skeleton at the time of calcification," said Dr Jan Fietzke, a physicist at GEOMAR and co-author of the study, which has been published in the Scientific Reports journal.

Dr Fietzke examined the skeleton which had been formed several days to weeks before the sampling. By comparing them with the pH values in the surrounding water, the team was able to prove that the boron isotopes reflected the internal pH of the coral, and that it was different from the pH of the environment – meaning that pH regulation had indeed taken place. Based on this, the cores from corals several decades old are currently being analysed, so as to find out when and how quickly they adapted.

During the research, it was discovered that the Porites corals were able to maintain their pH values for decades, thereby counteracting the effects of climate change. However, this pH regulation is possible only up to a certain degree. According to Dr Wall, if the carbon dioxide concentrations exceed the projected levels for 2100, calcification and growth would decrease, causing these corals to reach their physiological limits.

Link to study:

http://www.nature.com/articles/srep30688